Page

1 2

page 2 of 2

The two witnesses whose testimony received the most attention were Wertham and Gaines. In many ways, these two personified the struggle over comic books in postwar America. Wertham played a central role in the comic book controversy, beginning with his attack on comic books in 1948. His credentials were impressive, and he was quickly embraced as a leading expert in the field of comics and juvenile delinquency and was often asked to testify in cases in state and federal courts. Wertham’s book summarizing his case against comics, Seduction of the Innocent, was published just before the Senate began its hearings on comics, and it was this material on which Wertham based his testimony. Gaines, who inherited his comics publishing business after his father died in a boating accident in 1947, was the most outspoken of the comic book publishers, and the media frequently interviewed him when they needed a quote from an industry representative. Gaines’s company, called Educational Comics in 1947, was publishing “kiddie comics” with names like Bouncy Bunny in the Friendly Forest. Gaines began to introduce new titles, and by the end of 1949 was publishing six love, crime, and western comics. In 1950, he changed the company name to Entertaining Comics and issued what became known as the “New Trend” comics, launching such horror titles as The Crypt of Terror and The Vault of Horror. The new titles sold well, and within a year E.C.’s financial problems were over. It was these titles that attracted the attention of critics such as Wertham and, as a result, the subcommittee.

Wertham testified on the afternoon of the first day of the hearings, followed by Gaines. Gaines originally had been scheduled to appear in the morning, but other witnesses apparently ran on longer than expected, pushing Gaines’ testimony until after lunch. After the committee reconvened, however, Wertham appeared to testify, and the committee moved him ahead of Gaines. Gaines later contended that the postponement of his appearance adversely affected his testimony. According to his biographer, Gaines was taking diet pills, and as the medication begain to wear off, fatigue set in. Gaines recalled: “At the beginning, I felt I was really going to fix those bastards, but as time went on I could feel myself fading away...They were pelting me with questions and I couldn’t locate the answers.”

The committee took a very respectful tone with Wertham, allowing him to make a long statement before beginning its questioning; moreover, most of the questions were meant simply to clarify, rather than challenge, any of his testimony. Wertham began by noting that his was the only large-scale study of comic books, and that he never received a subsidy for his work, nor had he ever accepted a fee for speaking about comic books. Wertham then challenged the subcommittee’s definition of crime and horror comic, arguing for a more encompassing view. For Wertham, it made “no difference whether the locale is western, or Superman or space ship or horror, if a girl is raped she is raped whether it is in a space ship or on the prairie.” Wertham singled Superman out, noting that the comic books aroused in children “phantasies [sic] of sadistic joy in seeing other people punished over and over again while you yourself remain immune.” Wertham called it the “Superman complex.” Much of his testimony was anecdotal evidence of the harm of comic book reading drawn from his book or from articles, with Wertham describing how children imitated violence they read about in comic books. For example, he told the senators of this incident in New York State: “Some time ago some boys attacked another boy and they twisted his arm so viciously that it broke in two places, and, just like in a comic book, the bone came through the skin.”

Wertham also used the hearings to clarify his stand on the effects of comics, stating without any doubt or reservation that comic books were “an important contributing factor in many cases of juvenile delinquency.” Even Wertham, whose position on the effects of comic books was more extreme than that of his colleagues, did not say they were the only cause of juvenile delinquency. “Now, I don’t say, and I have never said, and I don’t believe it, that the comic-book factor alone makes a child do anything,” he said. Other environmental factors were at work. But, he added, he had isolated comics as one factor of delinquency and his was “not a minority report.” Underlining where he differed from his colleagues, however, he contended the kind of child affected was “primarily the normal child...the most morbid children that we have seen are the ones who are less affected by comic books because they are wrapped up in their own phantasies [sic].”

Despite Wertham’s reputation, it was Gaines’s testimony that was given wide play in the media--including front-page coverage in the New York Times--primarily due to an exchange between Gaines and Kefauver that served to demonstrate in the minds of many the absurdity of the comic book industry’s defense of what they published. Asked to defend his stories, Gaines stressed they had an “O. Henry ending” and that it was important that they not be taken out of context. When Chief Counsel Herbert Hannoch asked if it did children any good to read such stories, Gaines replied: “I don’t think it does them a bit of good, but I don’t think it does them a bit of harm, either.” He maintained throughout the hearings that comics were harmless entertainment.

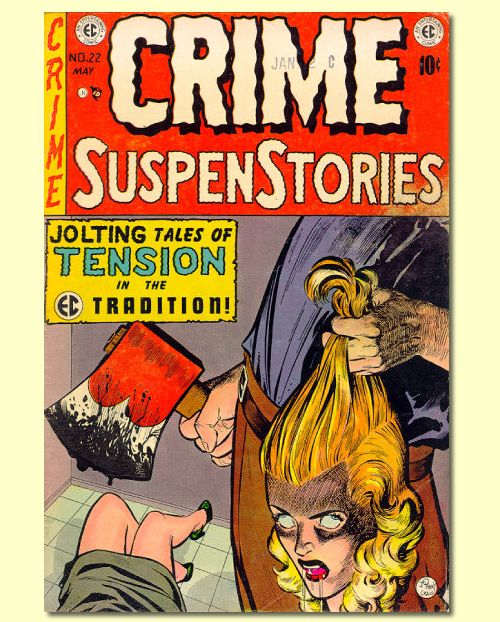

Then Herbert Beaser, Hannoch’s assistant, asked Gaines: “Is there any limit you can think of that you would not put in a magazine because you thought a child should not see or read about it?” Gaines said, “My only limits are the bounds of good taste, what I consider good taste.” With that statement, Gaines set himself up for the famous exchange with Senator Kefauver over a comic book cover. While questioning Gaines, Kefauver held aloft a comic book featuring a cover drawn by artist Johnny Craig for a comic titled Crime SuspenStories and remarked: “This seems to be a man with a bloody ax holding a woman’s head up which has been severed from her body. Do you think that is in good taste?” Having just said that he would publish anything he felt was in good taste, Gaines had no choice. He answered, “Yes, sir, I do, for the cover of a horror comic.” When Kefauver held up another cover showing a man choking a woman with a crowbar, Sen. Thomas Hennings halted that line of questioning, observing, “I don’t think it is really the function of our committee to argue with this gentleman.”

But the damage was done. Historian Maria Reidelbach notes that public sentiment turned decisively against the young publisher, as television and print news reports widely quoted the “severed head exchange.” The front-page story in the New York Times emphasized that testimony and carried the headline: “No Harm in Horror, Comics Issuer Says.” Such reports helped to confirm what book critics had been arguing all along--that comic book publishers were a decadent group out to make a profit at the expense of children, with little regard for the impact their crime and horror comics had on the youth of America. Common sense dictated that full-color comic book covers with gruesome illustrations were definitely not in good taste for children’s reading material.

Excerpted

from

Seal of Approval:

The History of the Comics Code

©1998

University Press of Mississippi

Used with permission.