Page

1 2

by Amy Kiste Nyberg

The

Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency conducted its investigation

of the comic book industry in the spring of 1954. The committee held three

days of hearings in New York City (the location selected because most

of the comic book publishers were based there), called twenty-two witnesses,

and accepted thirty-three exhibits as evidence. When it was all over,

the comic book industry closed ranks and adopted a self-regulatory code

that is still in effect today in modified form.

The

Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency conducted its investigation

of the comic book industry in the spring of 1954. The committee held three

days of hearings in New York City (the location selected because most

of the comic book publishers were based there), called twenty-two witnesses,

and accepted thirty-three exhibits as evidence. When it was all over,

the comic book industry closed ranks and adopted a self-regulatory code

that is still in effect today in modified form.

The driving force on the committee was Sen. Estes Kefauver. Sen. Robert Hendrickson was the chairman of the Senate subcommittee during the period in which the committee held its comic book hearings, but the committee is often referred to as the Kefauver committee, and when the 1954 elections returned control of Congress to the Democrats, Kefauver was given the chairmanship of the juvenile delinquency subcommittee. Under his direction, the committee wrote its report on the comic book industry, issued in March 1955, and continued its examination of violence and sex in the mass media with hearings on film and television. Kefauver, a Tennessee lawyer who was first elected to the House of Representatives in 1939, ran a successful race for a Senate seat in 1948. He rose to national prominence for his investigation of organized crime in the United States beginning in 1950. That investigation attracted a great deal of public interest and acquired a prestige probably unparalleled by any other congressional probe, and Kefauver used the publicity in his bid for the Democratic presidential nomination. While he lost the 1952 nomination to Adlai Stevenson, Kefauver hoped that the hearings on juvenile delinquency, a much less politically sensitive issue, might provide a platform for another try at the presidential nomination.

It was during the course of the Senate investigation of organized crime that Kefauver first turned his attention to comic books, gathering information on the comic book industry from a survey sent to judges of juvenile and family courts, probation officers, court psychiatrists, public officials, social workers, comic book publishers, cartoonists, and officers of national organizations who were interested in the issue. That survey was sent out in August 1950. The questionnaires were drawn up with the assistance of psychiatrist Fredric Wertham, who was acting as a consultant for the Senate committee. The survey included seven questions:

- Has juvenile delinquency increased in the years 1945 to 1950? If you can support this with specific statistics, please do so.

- To what do you attribute this increase if you have stated that there was an increase?

- Was there an increase in juvenile delinquency after World War II?

- In recent years, have juveniles tended to commit more violent crimes such as assault, rape, murder, and gang activities?

- Do you believe that there is any relationship between reading crime comic books and juvenile delinquency?

- Please specifically give statistics and, if possible, state specific cases of juvenile crime which you believe can be traced to reading crime comic books.

- Do you believe that juvenile delinquency would decrease if crime comic books were not readily available to children?

Of those responding to the survey, nearly 60 percent felt there was no relationship between comic books and juvenile delinquency, and almost 70 percent felt that banning crime comics would have little effect on delinquency. Since the report failed to make a strong case against comics, it was issued with little fanfare and the committee took no further action. Despite the fact that earlier Senate investigation failed to produce any recommendation or action, it provided a starting place when the judiciary subcommittee on juvenile delinquency turned its attention to the mass media.

As is the case with most congressional hearings, staff members for the juvenile delinquency subcommittee conducted an extensive background investigation before the actual hearings began. The groundwork for the comic book hearings was done by Richard Clendenen, executive director of the subcommittee. He was the chief of the juvenile delinquency branch of the United States Children’s Bureau and the bureau’s leading expert on delinquency. Prior to his position with the Children’s Bureau, Clendenen worked as a probation officer in a juvenile court and was an administrator at various institutions for emotionally disturbed children and delinquent children. In 1952, the new director of the Children’s Bureau, Martha Eliot, made juvenile delinquency her priority and created a Special Delinquency Project that Clendenen headed. Eliot loaned Clendenen’s services to the Senate subcommittee, partly because the subcommittee was underfunded and partly to give her agency a voice in the investigation; Clendenen joined the staff in August 1953. Clendenen began by requesting from the staff of the Library of Congress a summary of all studies published on the effects of comic books on children. He also sent several prominent individuals samples of the comic books under investigation and solicited their opinions on the effects of such material. He was aware of the work done by the New York Joint Legislative Committee to study comics and that done by the Cincinatti Committee on Evaluation of Comic Books, and their reports were included in the committee’s records.

The Post Office Department was given an extensive list of comic book titles, along with names of publishers, writers, and artists, to investigate. The purpose of the Post Office Investigation was to determine whether any of the titles listed had ever been ruled “unmailable” and whether any of the individuals listed had ever come under Post Office Department scrutiny. Postal regulations were sometimes used as a censorship tool by the federal government. The Post Office investigation failed to turn up any violations, and that line of inquiry was dropped. The subcommittee staff also conducted interviews with various publishers in order to learn more about the operation of the comic book industry. Publishers were asked to provide copies of the titles they published and circulation figures for each publication. In addition, the staff was interested in finding out about how a comic book was “processed” from the creation of the story idea through its execution, and who reviewed the manuscripts and artwork.

Once the preliminary investigations were complete, staff members drew up a list of witnesses. The list was finalized on Wednesday, April 21, shortly before the start of the hearings, and the staff provided committee members with brief background statements for each of the major witnesses, spelling out the position each was expected to take on comic books and delinquency and suggesting the direction that questioning might take. Among the witnesses were experts on juvenile delinquency, including psychiatrist Fredric Wertham, comic book publishers such as William Gaines, and a number of distributors and retailers who were to testify about the distribution and sale of comic books. The committee also heard from witnesses who had been active in other investigations of comic books, including James Fitzpatrick, then chairman of the New York committee to study comics, and E.D. Fulton, who engineered a ban on crime comic books in Canada.

The hearings opened with a statement from Senator Hendrickson, who outlined the purpose and goals of the committee. Hendrickson announced that the hearings would be concerned only with crime and horror comic books, acknowledging that authorities agreed the majority of comic books were “as harmless as soda pop.” He argued that freedom of the press was not at issue and that his committee did not intend to become “blue-nosed censors.” And he claimed the committee approached the issue with no preconceptions; rather, the task of the committee was to determine whether crime and horror comic books produced juvenile delinquency.

The testimony of the first witness, committee staffer Clendenen, set the tone of the hearings. He began his presentation by showing examples of the crime and horror comics under investigation by the committee. He had originally prepared a show of twenty-nine slides to accompany the plot summaries of several comic book stories, but due to time constraints he discussed only seven comic book titles, accompanied by thirteen slides. The slides consisted of both comic book covers and sample panels from individual stories contained in the books. Clendenen told the senators his examples were “quite typical” of crime and horror comics, but in fact he deliberately selected comic book titles that had already been singled out for criticism by Wertham and others. In addition, the plot summaries written by Clendenen emphasized the violence. With most of his examples, Clendenen included a count of how many people died violently in the comic book.

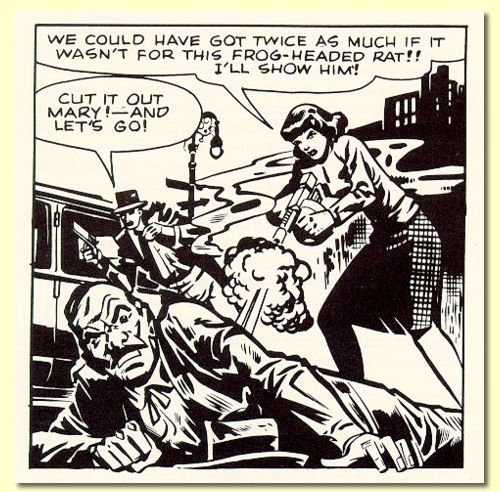

For example, while discussing “Frisco Mary,” a story from Crime Must Pay the Penalty (March 1954), Clendenen showed two slides, the cover of the comic, which had nothing to do with the story, and a single panel taken from page five of the story, which Clendenen described in his prepared statement as, “Shot of Frisco Mary using submachine gun on law officer.” The story is about Mary Fenner, known as “Frisco” Mary, and her gang. Rather than being a victim, like many women depicted in the crime stories, Mary takes charge of the gang and commits much of the violence in the story. In the scene Clendenen selected, Mary leads her gang in a bank robbery, and their crime is interrupted by the arrival of the sheriff. The lawman is shot by the gang member in the getaway car, and Mary steps up to finish off the job in the slide Clendenen presented, where she remarks: “We could have got twice as much if it wasn’t for this frog-headed rat!! I’ll show him!” She is chided by a fellow gang member for being too trigger-happy. After some careful detective work, police discover the gang’s hideout. The police take Mary and her husband, Frank, into custody. The rest of the gang, afraid that Frank will “rat them out,” break him out of jail and shoot him down. The police then shoot the gang members, remarking, “Well--that finishes the Fenner gang--and saves the state the cost of a trial.” Mary, the sole remnant of the gang, is tried and executed in the gas chamber.

Clendenen’s account of the story was as follows:

One story in this particular issue called “Frisco Mary” concerns an attractive and glamorous young woman who gains control of a California underworld gang. Under her leadership the gang embarks upon a series of hold-ups marked for their ruthlessness and violence. Our next picture shows Mary emptying her submachine gun into the body of an already wounded police officer after the officer has created an alarm and thereby reduced the gang’s take in a bank holdup to a mere $25,000. Now in all fairness it should be added that Mary finally dies in the gas chamber following a violent and lucrative criminal career.

This story is a good example ot the type of crime comics that critics found objectionable. The lead character, Mary Fenner, is extremely violent and kills without hesitation or remorse. Her victims are innocent, unarmed men who are foolish enough to get in her way. There is always a big monetary payoff for the crime, and the gang members escape unscathed (until the end of the story). The police, too, are violent men who do not hesitate to shoot the fleeing robbers in the back and then gloat. This story, like many, justifies the violence by making sure the criminals are punished in the end. But Mary’s fate is buried in a caption, without any illustration, and the end of the story, finishing with, “She breathed out her life in a California gas chamber--discovering, but too late--that crime must pay the penalty!” After nine pages of glorifying the violence and rewards of the criminal life, the short tag at the end of the story seems almost inconsequential.

Next, Clendenen introduced the survey of literature on comics and juvenile delinquency compiled by the Library of Congress, noting that the expert opinion and findings of the studies reflected a diversity of opinion regarding the effects of crime comics on children. The four experts testifying before the committee reflected that diversity. Two experts who took the position that crime comics were harmful were Harris Peck, a psychiatrist and director of the Bureau of Mental Health Services for the New York City Children’s Court, and Wertham, who of course had been campaigning for years for laws against comics. Two experts who asserted that there was little evidence of harm caused by the comics were Gunnar Dybwad, the executive director of the Child Study Association of America, and Lauretta Bender, a senior psychiatrist at Bellevue Hospital. One other group was invited to testify about the effects of comics--the comic book publishers themselves. The committee heard from four industry representatives: William M. Gaines, publisher of Entertaining Comics Group; William Friedman, publisher of Story Comics; Monroe Froehlich, Jr., business manager for Magazine Management Company, publishers of Marvel Comics; and Helen Meyer, vice president of Dell Publications.